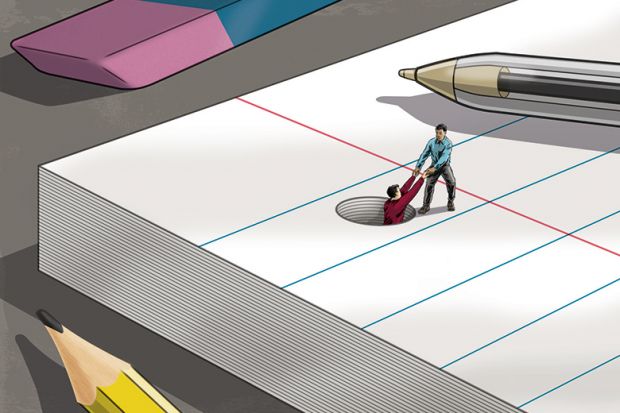

Most people need structure, accountability and discipline if they are to work productively. But this is exactly what disappears when highly qualified, often perfectionistic people start the rewarding but lengthy and lonely PhD process.

This is especially true in the humanities, where, in contrast to the more communal research environment that scientific teams enjoy, study is often solitary. I believe that universities can, and should, do much more to generate a sense of group motivation, camaraderie and peer support among early career scholars in the humanities.

I convene a group of postgraduate students and early career researchers to write together for three hours twice a week. After coffee, I ask everyone to share their goals for the first 75-minute session with their neighbour. Goals must be specific, realistic and communicable, such as writing 250 words or reworking a particularly problematic paragraph. I set an alarm and remind everyone not to check email or social media. When the alarm goes off, everyone checks in with their partner about whether or not they achieved their goal. After a break, we do it again. After our Friday morning sessions, we go for lunch together. And that’s it.

Yet the impact of the group in terms of writing productivity, reducing student stress and promoting a sense of community has been profound – beyond what even I had anticipated when I first introduced these sessions at the interdisciplinary Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities in October 2015. Since its beginning, the group has been enormously popular and is always oversubscribed. I have become convinced that such writing groups are an affordable and highly effective way of reducing early career isolation and improving mental health, and could be implemented more widely.

Participants reported the positive effects in two anonymous surveys for our humanities division. They value the sessions’ imposition of routine, realism about expectations and embodiment of the principle that thinking happens through, not before, writing (known as the “writing as a laboratory” model). Respondents were pleasantly surprised at their own productivity. One said: “I never thought I could accomplish so much in one hour, if I really committed, without interruptions”.

Another said: “It seems I lost the fear of finishing things when I was surrounded by other people.” Participants also reported adopting their newly established good habits outside the sessions.

Most evident, however, was respondents’ improved sense of morale and peer support. One noted that “the PhD can be such an isolating experience; it’s very calming to come to a place where, twice a week, we’re reminded that working independently doesn’t have to mean working alone”. Another referred to the group as “an invaluable resource that should be mandatory for all PhDs”.

The writing group offers, for six hours a week, what most workers get every day: a start time, a stop time and peer pressure not to procrastinate on the internet. Over a term’s worth of attendance, this produces serious results. One participant had “rewritten a draft thesis chapter, written a conference abstract, edited two reviews for an online publication, finished two book reviews and edited several chapters of a volume”.

My role in the group varies between friend, peer, disciplinarian, mentor, stand-in supervisor, and a regular fixture offering some stability and continuity. If people don’t show up, I hold them accountable. If they are struggling with a piece of writing, I talk them through it. The group has unexpectedly become an informal forum for all the academic questions we’re not sure who else to ask about, and has therefore had a serious impact on pastoral care through peer support.

As someone who worked long hours through the four years of my PhD – in exhausting periods of “binge writing” and unnecessarily time-consuming revisions – I am now a vocal advocate of short bursts of focused attention and writing as a routine practice, with mandatory time off from academic work. One survey respondent noted that the group “has given me the sense that I have a working week and am not expected to work 24/7; it has helped me treat my degree as a job”.

As the group has developed, I have investigated strategies to make the sessions more effective. One idea was to organise a manual or sensory activity (colouring in or listening to music, for instance) during the break; another was to make participants set regular goals on index cards and to add a gold star when they achieve them. Writing marathons – two three-hour sessions, separated by lunch – are useful for meeting end-of-term deadlines. The combination of accountability and reward (group celebrations at the end of a goal period, or when somebody submits their dissertation) motivates participants both to push themselves and to be pleased with their progress.

There is surprisingly little literature on the benefits of writing in group settings. Very helpful texts, such as Eviatar Zerubavel’s The Clockwork Muse (1999) and Paul Silvia’s How to Write a Lot (2007), advocate scheduled writing, goal setting and monitoring progress, but do not address the high levels of self-discipline needed for regular independent writing that a group provides. Meanwhile, the literature considering writing groups, such as Rowena Murray and Sarah Moore’s The Handbook of Academic Writing (2006) or Claire Aitchison and Cally Guerin’s volume Writing Groups for Doctoral Education and Beyond (2014), promotes them for collaborative writing or peer review purposes, rather than improved morale and community.

Amid mounting demands for “outputs” and increasing evidence of chronic stress and mental health problems among academics, having an academic writing group at every university could be a simple yet powerful way of making the task of writing more productive and rewarding for the next generation of scholars.

Alice Kelly is the Harmsworth postdoctoral research fellow at the Rothermere American Institute at the University of Oxford.

Fonte: The World University Rankings